Night market

Leisure Activities

Street food

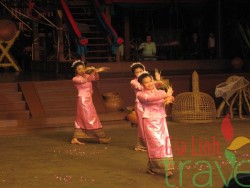

Traditional dancing

A penchant for khwam sanuk combines with a natural gregariousness to ensure that both spontaneous and formal leisure activities are vital parts of the Thai village’s social fabric.

Rice cultivation demands consistent hard work, but the communal gatherings that result set the stage for all types of group activities from feasting to courting. Some evenings after a hard day’s work, many villagers, instead of going to bed, gather around bonfires to talk. Young people sing and court. Older people chat, smoke, and drink homemade rice liquor, a mild or potent brew depending on the brewer’s skill and the ingredients at hand.

There may be a rhyming song contest and a lot of friendly banter between old and young as individuals try to outdo each other in composing choruses with familiar themes. Local musicians may play reed instruments, bamboo flutes, hand cymbals, and drums t o accompany singers, providing both inspiration and humor. Ordinations, particularly when a number of families pool resources for a group ceremony, are often celebrated with similar festivity. Enormous feasts are prepared. Electric generators may be rented, a band organized, and a folk dance drama troupe engag ed to keep revelers spellbound until the early hours with satiric comic opera performances featuring outrageous puns and double entendres, sly ribaldry, and popular folk songs.

Throughout the year, villagers share a common interest in gambling, traveling (pai thieo), and national lottery excites imaginations in every province, as do cockfights and such exotic competitions as fish and beetle fighting. Card games are a pastime favored by both sexes and almost everyone can play Thai chess.

Pai thieo by foot, boat, bus, motorbike, or rail is a favorite way to relax when time allows. Traveling makes the villager less insular and personal relations with family and friends are treasured as much for the opportunities they afford for travel as for the affection upon which they are based.

Besides national celebrations, there are regional festivals like the northeast Ngan Hae Bang Fai, or skyrocket festival, in May or June of each year. Traditionally a time of letting off steam, the festival’s high point comes when, amid much merrymaking, villagers fire homemade rockets, some of them 20 meters tall, to ensure a plentiful rainfall for the forthcoming rice season.

Takro and kite flying are popular traditional sports. Takro is played by a loosely formed circle of men who use their feet, knees, thighs, chests, and shoulders to acrobatically pass a woven rattan ball to one another, endeavoring to keep it in the air as long as possible and eventually kick it into a basket hanging high above their heads. (There is also a professional version of takro, known as sepak takro, which is played by teams from various ASEAN countries.)

Kites are flown mostly during the breezy hot season. Popular in Thailand since at least the founding of Sukhotai, kites have been used effectively in warfare: an Ayutthaya governor quelled a northeast city-state’s rebellion in 1690 by flying huge kites, called chulas, over the besieged city and bombing it into submission with jars of explosives.

In addition to being an individual pleasure, kite flying can be a competitive sport. Opposing teams fly male (chula) and female (pakpao) kites in a surrogate battle of the sexes. The small agile pakpaos try to bring down the more cumbersome chula, whil e the male kite seeks to snare the female kites and bring them back into male territory.

During temple fairs, another popular sport is the unique martial art of Thai boxing. A form of self-defense developed during the Ayuthaya period, Thai boxing forbids biting, spitting, or wrestling. On the other hand, the contestants may punch, kick, an d shove, and unrestrainedly use their bare feet, legs, knees, elbows, shoulders, and fists to elbow smash to the eyes, a knee in the stomach, of a whiplash kick in the chest can immediately floor the sturdiest of opponents. Nowadays boxers wear conventional boxing gloves, a somewhat humane development considering that less than 50 years ago they customarily bound their fists with hemp which contained liberal quantities of ground glass.

The major portion of Thai cuisine is highly spiced and chili hot, thanks to the addition of a variety of chilies, large and small, some more potent than others. The burning sensation of Thai chilies has caused much fanning of mouths by stunned foreigners on their first sampling but increased experience often brings enthusiastic approval, as attested by the popularity of Thai restaurants today throughout the world.

The ideal traditional Thai meal aims at being a harmonious blend of spicy, subtle, sweet, and sour and is meant to be appealing to eye, nose, and palate. A large central bowl of rice may be accompanied by a clear soup (perhaps bitter melons stuffed with minced pork), a steamed dish (mussels in curry sauce), a fried dish (fish with ginger(, a hot salad (sliced beef on a bed of greens with chilies, onions, mint, lemon juice, and more chilies), and a variety of sauces and condiments, of which the most essential is nam pla (fermented fish sauce), into which food can be dipped. This is normally followed by a sweet dessert (bananas coated with sugared coconut and deep fried, for example) and, finally, fresh fruit (such as mangoes, durian, papaya, jackfruit t, watermelon, and many more) of which Thailand boasts a year-round supply

Thai cuisine

Thailand’s distinctive cuisine is becoming more and more popular throughout the world.

Food varies from region to region, with modifications of standard dishes and also local specialties. In Chiang Mai, for example, the food is generally milder than that of the central region; naem, a spicy pork sa usage, is a northern delicacy.

Northeastern food tends to be very spicy, with explosive salads and special broiled, minced meat dishes mined with miniature, high-voltage green chillies. Glutinous rice is more popular in this region than steamed rice and exotic dishes like fried ants and grasshoppers and frog curry are not uncommon.

Southern cuisine makes delicious use of the creatures which team in the nearby seas. Lobsters, crabs, scallops, fish, and squid are common ingredients and unusual delicacies like jellyfish salad can also be found. In the southernmost provinces, where t here is a large Muslim community, sweet, mild, and spicy curries abound.

Foreign foods have also found a place in the Thai diet. Some of these go far back into history, like the egg-based Portuguese sweets which were introduced in the Ayutthaya period, while others like bread and cake are more recent acquisitions.

To please the eye, Thai cooks pursue the ancient art of fruit and vegetable caring to transform tables into visual feasts. Originally an aristocratic art practiced at the royal court, vegetable carving flourished throughout the Ayutthaya period, when a deft hand could fashion a white radish rose in a matter of minutes. It reached its zenith during the Bangkok reign of King Rama II when court ladies created flowers, fish, vases, bowls, and other decorative objects from watermelons, cucumbers, tomatoes, onions, and other unlikely garden produce. On a somewhat broader scale the art is still practiced today: there are few more charming surprises than discovering tomato roses and cucumber primroses with a local fast lunch.