Laos ethnic group

Laos Ethnic Group

Laos ethnic group

Laos ethnic group

Laos has a diverse geography and population. The north is a rich tapestry of ethnic minorities, and Lao people themselves support cultural and ethnic enclaves that differ from region to region, hill to plain. The mighty Mekong River and its tributaries form the spine of the land, and the country boasts vast tracts of deep jungle, open farmland, and even tropical river islands. Remnants of ancient civilizations are here as well, including the mysterious Plain of Jars in Phonsavan and Wat Phu, a Hindu site that predates Angkor Wat near the Cambodia border. Luang Prabang, the biggest burg up north, is a quiet city of colonial French architecture and was named a UNESCO World Heritage site.

Laos People

One of South East Asia’s most ethnically diverse countries, Laos has long defied the best efforts of anthropologists and linguists to classify its complex array of ethnicities and sub-ethnicities, many of which utilise several different names and synonyms given to them by the government or by other ethnic groups.

It is identified that there is about 50 rich, ethnic groups in Laos. For symplification, however, they are normally devided according to their geographical location: Lao Loum (Lao from the plains; corresponding to Lao, Lu, Phuan and other Tai-speaking Austro-Thai language family peoples); Lao Theung (from the hills, embracing all Austro-Asiatic language family peoples); Lao Soung (from the mountains; comprising Hmong-Mien peoples of the Austro-Thai language family and all Sino-Tibetan language family peoples).

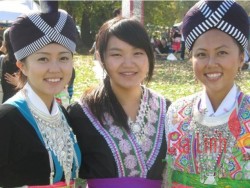

Laos hill tribes – Laos Soung

The Lao Soung (literally, the “high Lao”) are comparative newcomers to Laos, having migrated from China at the beginning of the nineteenth century and settled on the only land available to them, at elevations over 1000m above sea level. Among the Lao Soung are the country’s most colourfully dressed ethnic groups, such as the Hmong, Mien, Lahu and Akha. You may well encounter these peoples trading at lowland markets or sometimes walking along the roadside in single file, but seeing a Lao Soung village at first hand is often one of the highlights of a trip to Laos, providing a chance to reflect on an age-old existence that, for some travellers, seems to compare favourably with their own.

The Hmong

Most numerous among the Lao Soung are the Hmong, with a population of approximately 200,000. Their apparel is among the most colourful to be found in Laos, and the Hmong are divided into several sub-groups including the White Hmong, Red Hmong, Blue Hmong and Striped Hmong named for the predominant colour of their costumes. Collectors prize Hmong silver jewellery; Hmong babies receive their first silver necklace at the age of one month, and by the time they are adults they will have several kilogrammes of silver jewellery, most of which is cached until special occasions such as Hmong New Year. Their written language uses Roman letters and was devised by Western missionaries.

The Lahu

The Lahu inhabit areas of northwestern Laos, as well as Thailand and Burma. A branch of the Lahu tribe known as the Lahu Na, or Black Lahu, are known first and foremost for their hunting skills. Formerly they used crossbows but now manufacture their own muzzle-loading rifles which they use to hunt birds and rodents. Old American M1 carbines and Chinese-made Kalashnikov rifles are used to bring down larger game, and Lahu hunters are sometimes seen at the side of the road displaying a freshly bagged deer or boar for sale.

The Mien

The Mien are linguistically related to the Hmong and also immigrated into Laos from China, but their culture is much more Sinicized; the Mien use Chinese characters to write their documents and worship Taoist deities. Like the Hmong, they cultivate opium, which they trade for salt and other necessities that are not easily obtained at high elevations, and are known to be astute traders. It’s estimated that nearly half the country’s Mien population fled after the communist victory, eventually settling in the USA and France; today Xainyabouli province, northwest of Vientiane, has the largest population of Mien in Laos.

The costume of Mien women is perhaps Laos’s most exotic, involving intricately embroidered pantaloons worn with a coat and turban of indigo blue. The most striking feature is a woolly red boa, attached to the collar and running down the front of their coat.

The Akha

The Akha are another of the highlands’ stunning dressers. They believe that art is more appropriately displayed on one’s body, as opposed to hanging it on walls. Catching a first glimpse of the Akha women’s distinctive headgear – covered with rows of silver baubles and coins – is surely one of the highlights of many a Lao visit.

Speakers of a Tibeto– Burman language, the Akha began migrating south from China’s Yunnan province to escape the mayhem of the mid-nineteenth century Muslim Rebellion. This was followed by another exodus after the Chinese communist victory in 1949 and again during the Cultural Revolution. They now inhabit parts of Vietnam, Burma (Myanmar) and Thailand as well as Laos, where they are found mainly in Phongsali and Louang Namtha provinces.

Akha villages are easily distinguished by the elaborate “spirit gate” leading into the village. This gate is hung with woven bamboo “stars” that block spirits, plus talismanic carvings of helicopters, aeroplanes and even grenades, as well as crude male and female effigies with exaggerated genitalia. The Akha are animists and, like the Hmong, rely on a village shaman and his rituals to help solve problems of health and fertility or provide protection against malevolent spirits. Chickens and pigs are sometimes sacrificed and chicken bones are utilized to divine the future. As with the Hmong and Mien, the Akha use opium to soothe the day’s aches and pains, and some Akha also use massage to the same effect. The Akha raise dogs as pets as well as for food, but do not eat their own pets; dogs that will be slaughtered for their meat are bought or traded from another village.

The Akha are fond of singing and often do so while on long walks to the fields or while working. Some songs are specially sung for fieldwork but love ballads are also popular. There is even a sort of “Akha blues”: songs about poor Akha villagers struggling through life while surrounded by rich neighbours.

The lowland Laos – Laos Loum

The so-called Lao Loum (or lowland Lao) live at the lowest elevations and on the land best suited for cultivation. For the most part, they are the ethnic Lao, a people related to the Thai of Thailand and the Shan of Burma. The lowland Lao make up between fifty and sixty percent of the population, and are the group for which the country is named. They, like their Thai and Shan cousins, prefer to inhabit river valleys, live in dwellings that are raised above the ground, and are adherents of Theravada Buddhism.

Of all the ethnicities found in Laos, the culture of the lowland Lao is dominant, mainly because it is they who hold political power. Their language is the official language, their religion is the state religion and their holy days are the official holidays. As access to a reliable water source is key to survival and water is abundant in the river valleys, the ethnic Lao have prospered. They have been able to devote their free time – that time not spent securing food – to the arts and entertainment, and their culture has become richer for it. Among the cultural traits by which the Lao define themselves are the cultivation and consumption of sticky rice as a staple, the taking part in the animist ceremony known as basi, and the playing of the reed instrument called the khaen. Akin to the ethnic Lao are the Tai Leu, Phuan and Phu Tai, found in the northwest, the northeast and mid-south respectively.

The Tai Leu of Laos are originally from China’s Xishuangbanna region in southern Yunnan, where nowadays they are known as the “Dai minority”. In Laos, their settlements stretch from the Chinese border with Louang Namtha province, through Oudomxai and into Xainyabouli; among foreign visitors, the best known Tai Leu settlement is Muang Sing. The Tai Leu are Theravada Buddhists and, like the Lao, they placate animist spirits. They are known to perform a ceremony similar to the basi ceremony which is supposed to reunite the wayward souls of their water buffalo. They are also skilled weavers whose work is in demand from other groups that do not weave, such as the Khamu.

The Phuan are in the same historical predicament as such Southeast Asian peoples as the Mon and Cham: they were once a recognized kingdom, but are now largely forgotten. The kingdom’s territory, formerly located in the province of Xiang Khuang (the capital of which was formerly known as Muang Phuan), was at once coveted by the Siamese and Vietnamese. Aggression from both sides as well as from Chinese Haw bandits left the kingdom in ruins and the populace scattered. A British surveyor in the employ of a Siamese king reached Muang Phuan in the 1880s and remarked that the Phuan “exhibited refinement in all they did, but their elegant taste was of no avail against the rude barbarian”. To this day, there are villages of Phuan as far afield as central Thailand, inhabited by the descendants of Phuan villagers who were taken captive by the Siamese during military campaigns over a hundred years ago.

The Phuan are Theravada Buddhists, but once observed an impromptu holy day known as kam fa. When the first thunder of the season was heard, all labours ceased and villagers avoided any activity that might cause even the slightest noise. The village’s fortune was then divined based on the direction from which the thunder was heard.

The Phu Tai of Savannakhet and Khammouane provinces are also found in the northeast of Thailand. They are Theravada Buddhists and have assimilated into Lao culture to a high degree, although it is still possible to recognize them by their dress on festival days. The predominant colours of the Phu Tai shawls and skirts are an electric purple and orange with yellow and lime-green highlights.

Other Tai peoples related to the Lao are the so-called “tribal Tai”, who live in river valleys at slightly higher elevations and are mostly animists. These include the rather mysteriously named Tai Daeng (Red Tai), Tai Khao (White Tai) and Tai Dam (Black Tai). Theories about nomenclature vary. It is commonly surmised that the names were derived from the predominant colour of the womenfolk’s dress, but others have suggested that the groups were named after the river valleys in northern Vietnam where they were thought to have originated. These Tai groups were once loosely united in a political alliance called the Sipsong Chao Tai or the Twelve Tai Principalities, spread over an area that covers parts of northwestern Vietnam and northeastern Laos. The traditional centre was present-day Dien Bien Phu, known to the Tai as Muang Theng. When the French returned to Indochina after World War II, they attempted to establish a “Tai Federation” encompassing the area of the old Principalities. The plan was short-circuited by Ho Chi Minh who, after defeating the French, was able to manipulate divisions between the Tai groups in order to gain total control.

The Tai Dam are found in large numbers in Houa Phan and Xiang Khouang provinces, but also inhabit northern Laos as far west as Louang Namtha. This ethnic group are principally animists and have a system of Vietnamese-influenced surnames that indicate political and social status. The women are easily recognized by their distinctive dress: long-sleeved, tight-fitting blouses in bright, solid colours with a row of butterfly-shaped silver buttons down the front and a long, indigo-coloured skirt. The outfit is completed with a bonnet-like headcloth of indigo with red trim.

Mon– Khmer groups – Laos Theung

The ethnic Lao believe themselves and their ethnic kin to have inhabited an area that is present-day Dien Bien Phu in Vietnam before migrating into what is now Laos. Interestingly, there is historical evidence to support their legends. As the Lao moved southwards they displaced the original inhabitants of the region. Known officially as the Lao Theung (theung is Lao for “above”), but colloquially known as the kha (“slaves”), these peoples were forced to resettle at higher elevations where water was more scarce and life decidedly more difficult.

The Khamu of northern Laos are thought to number around 350,000, making them one of the largest minority groups in Laos. Speakers of a Mon– Khmer language, they have assimilated to a high degree and are practically indistinguishable from the ethnic Lao to outsiders. Their origins are obscure. Some theorize that the Khamu originally inhabited China’s Xishuangbanna region in southern Yunnan and migrated south into northern Laos long before the arrival of the Lao. The Khamu themselves tell legends of their being northern Laos’s first inhabitants and of having founded Louang Phabang. Interestingly, royal ceremonies once performed annually by the Lao king at Louang Phabang symbolically acknowledged the Khamu’s original ownership of the land. The Khamu are known for their honesty and diligence, though in the past they were easily duped by the lowland Lao into performing menial labour for little compensation. Their lack of sophistication in business matters and seeming complacency with their lot in life probably led to their being referred to as “slaves” by the lowland Lao. Unlike other groups in Laos, the Khamu are not known for their weaving skills and so customarily traded labour for cloth. The traditional Khamu village has four cemeteries: one for adults who died normal deaths, one for those who died violent or unnatural deaths, one for children and one for mutes.

A large spirit house located outside the village gates attests to the Khamu belief in animism. Spirits are thought to inhabit animals, rice and even money. Visitors to the village must call from outside the village gate, enquiring whether or not a temporary village taboo is in place. If so, then a visitor may not enter, and water, food and a mat to rest on will be brought out by the villagers. If there is no taboo in effect, male visitors may lodge in the village common-house if an overnight stay is planned, but may not sleep in the house of another family unless a blood sacrifice is made to the ancestors. There is no ban on women visitors staying the night in a Khamu household as it is thought to be the property of the women residents.

The village common-house also serves as a home for adolescent boys, and it is there that they learn how to weave baskets and make animal traps as well as become familiar with the village folklore and taboos. The boys may learn that the sound of the barking deer is an ill omen when a man is gathering materials with which to build a house, or that it is wrong to bring meat into the village from an animal that has been killed by tiger or has died on its own. Young Khamu men seem to be prone to wanderlust, often leaving their villages to seek work in the lowlands. Their high rate of intermarriage with other groups during their forays for employment has contributed to their assimilation.

Another Mon– Khmer-speaking group which inhabits the north, particularly Xainyabouli province, are the Htin. They excel at fashioning household implements, particularly baskets and fish traps, from bamboo (owing to a partial cultural ban on the use of any kind of metal), and are known for their vast knowledge of the different species of bamboo and their respective uses.

Linguistically related to the Khamu and Htin are the Mabri, Laos’s least numerous and least developed minority. Thought to number less than one hundred, the Mabri have a taboo on tilling the soil which has kept them semi-nomadic and impoverished. Half a century ago they were nomadic hunter-gatherers who customarily moved camp as soon as the leaves on the branches that comprised their temporary shelters began to turn yellow. Known to the Lao as kha tawng leuang (“slaves of the yellow banana leaves”) or simply khon pa (“jungle people”), the Mabri were thought by some to be naked savages or even ghosts, and wild tales were circulated about their fantastic hunting skills and ability to vanish into the forest without a trace. The Mabri were said to worship their long spears, making offerings and performing dances for their weapons to bring luck with the hunt. Within the last few decades, however, they have given up their nomadic lifestyle and now work for other groups, performing menial tasks in exchange for food or clothing.

The Bolaven Plateau in southern Laos is named for the Laven people, yet another Mon– Khmer-speaking group whose presence predates that of the Lao. The Laven were very quick to assimilate the ways of the southern Lao, so much so that a French expansionist and amateur ethnologist who explored the plateau in the 1870s found it difficult to tell the two apart. Besides the Laven, other Mon– Khmer-speaking minorities are found in the south, particularly in Savannakhet, Salavan and Xekong provinces. Among these are the Bru, who have raised the level of building animal traps and snares to a fine art. The Bru have devised traps to catch, and sometimes kill, everything from mice to elephants, including a booby-trap that thrusts a spear into the victim.

The Gie-Trieng of Xekong are one of the most isolated of all the tribal peoples, having been pushed deep into the bush by the rival Sedang tribe. The Gie-Trieng are expert basket weavers and their tightly woven quivers, smoked a deep mahogany colour, are highly prized by collectors. The Nge, also of Xekong, produce textiles bearing a legacy of the Ho Chi Minh Trail that snaked through their territory and of American efforts to bomb it out of existence. Designs on woven shoulder bags feature stylized bombs and fighter planes, and men’s loincloths are decorated with rows of tiny lead beads, fashioned from the munitions junk that litters the region.

The Alak and Katu have of late been brought to the attention of outsiders by Lao tour agencies who are eager to cash in on the tribal custom of sacrificing water buffalo, in a ceremony reminiscent of the final scene in the film Apocalypse Now. The Katu are said to be a very warlike people and, as recently as the 1950s, carried out human sacrifices to placate spirits and ensure a good harvest. The ethnic Lao firmly believe that these southern Mon– Khmer groups are adept at black magic, and advise visitors to keep a cake of fragrant soap on their person to foil the sorcery of tribal witchdoctors.